Sunday, May 27, 2012

Preparing for Total Global Economic Collapse

Preparing for an economic collapse

Keiser Report, Guest Reggie Middleton on ponzi economics (02Apr12)

Great job Reg, though you can't predict the outcomes based on every action gets a certain reaction. You aren't an insider so you don't know the true "planned action". You can only deduce on a realtime basis, what the reaction is after a said occurence or rumor of claim of future action.

Sifting through bullshit, wears me out. KEep plugging Reggie, you might find a penny in that pile of shit, yet.

div dir="ltr" style="text-align: left;" trbidi="on">

Saturday, May 12, 2012

When greed takes hold, finance in all its forms is undone.

When greed takes hold, finance in all its forms is undone.

FINANCIAL INNOVATION HAS a dreadful image these days. Paul Volcker, a former chairman of America’s Federal Reserve, who emerged from the 2007-08 financial crisis with his reputation intact, once said that none of the financial inventions of the past 25 years matches up to the ATM. Paul Krugman, a Nobel prize-winning economist-cum-polemicist, has written that it is hard to think of any big recent financial breakthroughs that have aided society. Joseph Stiglitz, another Nobel laureate, argued in a 2010 online debate hosted by The Economist that most innovation in the run-up to the crisis “was not directed at enhancing the ability of the financial sector to perform its social functions”.

FINANCIAL INNOVATION HAS a dreadful image these days. Paul Volcker, a former chairman of America’s Federal Reserve, who emerged from the 2007-08 financial crisis with his reputation intact, once said that none of the financial inventions of the past 25 years matches up to the ATM. Paul Krugman, a Nobel prize-winning economist-cum-polemicist, has written that it is hard to think of any big recent financial breakthroughs that have aided society. Joseph Stiglitz, another Nobel laureate, argued in a 2010 online debate hosted by The Economist that most innovation in the run-up to the crisis “was not directed at enhancing the ability of the financial sector to perform its social functions”.

Most of these critics have market-based innovation in their sights. There is an enormous amount of innovation going on in other areas, such as retail payments, that has the potential to change the way people carry and spend money. But the debate—and hence this special report—focuses mainly on wholesale products and techniques, both because they are less obviously useful than retail innovations and because they were more heavily implicated in the financial crisis: think of those evil credit-default swaps (CDSs), collateralised-debt obligations (CDOs) and so on.

For a demonstration, look at Peterborough. The cathedral city in England’s Cambridgeshire is known for its railway station and an underachieving football club nicknamed “the Posh”. But it is also the site of a financial experiment that its backers hope will have big ramifications for the way public services are funded.This debate sometimes revolves around a simple question: is financial innovation good or bad? But quantifying the benefits of innovation is almost impossible. And like most things, it depends. Are credit cards bad? Or mortgages? Is finance as a whole? It is true that some instruments—for example, highly leveraged ones—are inherently more dangerous than others. But even innovations that are directed to unimpeachably “good” ends often bear substantial resemblances to those that are now vilified.

Peterborough is where the proceeds of the world’s first “social-impact bond” are being spent. This instrument is not really a bond at all but behaves more like equity. In September 2010 an organisation called Social Finance raised £5m ($7.8m) from 17 investors, both individuals and charities. The money is being used to pay for a programme to help prevent ex-prisoners in Peterborough from reoffending. Reconviction rates among the prisoners recruited to the scheme will be measured against a national database of prisoners with a similar profile, and investors will get payouts from the Ministry of Justice if the Peterborough cohort does better than the rest. If all goes well, the first payouts will be made in 2013.

The scheme is getting lots of attention, and not just in Britain. A mixture of social and financial returns is central to a burgeoning asset class known as “impact investing”. Linking payouts to outcomes is attractive to governments keen to husband scarce resources. And if service providers like the people running the Peterborough prisoner-rehabilitation scheme can get a lump sum up front, they can plan ahead without bearing any financial risk. There is talk of introducing social-impact bonds in Australia, Canada and the United States.

Here, surely, is a financial innovation that even the industry’s critics would agree is worth trying. Yet in fundamental ways an ostensibly “good” instrument like a social-impact bond is not so different from its despised cousins. First, at its root the social-impact bond is about creating a set of cashflows to suit the needs of the sponsor, the provider and the investor. True, the investors in the Peterborough scheme may be more willing than the average individual or pension fund to sacrifice financial returns for social benefits. But as Franklin Allen of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania and Glenn Yago of the Milken Institute, a think-tank, argue in their useful book, “Financing the Future”, the thread that runs through much wholesale financial innovation is the creation of new capital structures that align the interests of lots of different parties.

Second, the social-impact bond is based on the concept of risk transfer, in this case from the government to financial investors who will get paid only if the scheme is successful. Risk transfer is also one of the big ideas behind securitisation, the bundling of the cashflows from mortgages and other types of debt on lenders’ books into a single security that can be sold to capital-markets investors. The credit-default swap is an even simpler risk-transfer instrument: you pay someone else an insurance premium to take on the risk that a borrower will default.

Third, even at this early stage the social-impact bond is grappling with the difficulties of measurement and standardisation. An obvious example is the need to create defined sets of measurements in order to work out what triggers a payout—in this case, the comparison between the Peterborough prisoners and a control group of other prisoners in a national database. Across finance, standardisation—around contracts, reporting, performance measures and the like—is what enables buyers and sellers to come together quickly and new markets to take off.

Neither angels nor demons

For all the similarities, there are two big differences between the social-impact bond and other, less lauded financial instruments. The first is that the new tool has been designed explicitly for a social purpose. But ask a pensioner how much money he wants to put into prisoner rehabilitation, and it isn’t likely to be all that much.

Whether protecting a retirement pot or signalling problems with a government’s debt burden, finance can be “socially useful” (to use a phrase popularised by Adair Turner, the outgoing chairman of Britain’s Financial Services Authority) without being obviously social. Lord Turner himself acknowledged that in a speech he gave in London in 2009: “It is in the nature of markets that there are some things which are indirectly socially useful but which in the short term will look to the external world like pure speculation.”

Many people point to interest-rate swaps, which are used to bet on and hedge against future changes in interest rates, as an example of a huge, well-functioning and useful innovation of the modern financial era. But there are more contentious examples, too. Even the mention of sovereign credit-default swaps, which offer insurance against a government default, makes many Europeans choke. There are some specific problems with these instruments, particularly when banks sell protection on their own governments: that means a bank will be hit by losses on its holdings of domestic government bonds at the same time as it has to pay out on its CDS contracts. But in general a sovereign CDS has a useful signalling function in an area tilted heavily in favour of governments (which do not generally have to post collateral and can bully domestic buyers into investing).

When bubbles froth, innovations are used inappropriately—to take on exposures that should not have been, to manufacture risk rather than transfer it, to add complexity

The second difference is that social-impact bonds are still in their infancy, whereas other crisis-era innovations were directly involved in a gigantic financial crisis. There are questions to answer about their culpability. A few products from that period do look inherently flawed. Only the bravest are prepared to defend the more exotic mortgage products that sprouted at the height of America’s housing bubble as lenders found ever more creative ways to bring unaffordable houses within reach. Finance professionals almost blush to recall an instrument called the constant-proportion debt obligation, a 2006 invention of ABN AMRO that added leverage when it took losses in order to make up the shortfall. The end of the structured investment vehicle (SIV), an off-balance-sheet instrument invented to game capital rules, is not much lamented. And the complexity of the “CDO-squared” has been widely condemned.

But even now it is hard to find fault with the concept, as opposed to the practical application, of many of the most demonised products. The much-criticised CDO, which pools and tranches income from various securities, is really just a capital structure in miniature. Risk-bearing equity tranches take the first hit when things go wrong, and more risk-averse investors are more protected from losses. (Euro-zone leaders like the idea enough to have copied it with their plans for special-purpose investment vehicles for peripheral countries’ sovereign debt.) The real problem with the CDOs that blew up was that they were stuffed full of subprime loans but treated by banks, ratings agencies and investors as though they were gold-plated.

As for securitisation and credit-default swaps, it would be blinkered to argue they have no problems. Securitisation risks giving banks an incentive to loosen their underwriting standards in the expectation that someone else will pick up the pieces. CDS protection may similarly blunt the incentives for lenders to be careful when they extend credit; and there is a specific problem with the way that the risk in these contracts can suddenly materialise in the event of a default.

But the basic ideas behind both these two blockbuster innovations are sound. India, with a far more conservative financial system than America, allowed its first CDS deals to be done in December, recognising that the instrument will help attract creditors and build its domestic bond market. Similarly, securitisation—which worked well for decades—allows banks to free up capital, enabling them to extend more credit, and helps diversification of portfolios as banks shed concentrations of risks and investors buy exposures that suit them. “Securitisation is a good thing. If everything was on banks’ balance-sheets there wouldn’t be enough credit,” says a senior American regulator.

Rather than asking whether innovations are born bad, the more useful question is whether there is something that makes them likely to sour over time.

Greed is bad

There is an easy answer: people. When bubbles froth, greedy folk use innovations inappropriately—to take on exposures that they should not, to manufacture risk rather than transfer it, to add complexity in order to plump up margins rather than solve problems. But in those circumstances old-fashioned finance goes mad, too: for every securitisation stuffed with subprime loans in America, there was a stinking property loan sitting on the balance-sheet of an Irish bank or a Spanish caja. “Duff credit analysis is always the cause of the problem,” says Simon Gleeson of Clifford Chance, a law firm.

This argument has a lot of power. When greed takes hold, finance in all its forms is undone. Yet blaming the worst outcomes of financial innovation on human frailty is hardly helpful. This special report will point to the features of financial innovations that can turn them into troublemakers over time and show how these can be managed better.

In simple terms, finance lacks an “off” button. First, the industry has a habit of experimenting ceaselessly as it seeks to build on existing techniques and products to create new ones (what Robert Merton, an economist, termed the “innovation spiral”). Innovations in finance—unlike, say, a drug that has gone through a rigorous approval process before coming to market—are continually mutating. Second, there is a strong desire to standardise products so that markets can deepen, which often accelerates the rate of adoption beyond the capacity of the back office and the regulators to keep up.

As innovations become more and more successful, they start to become systemically significant. In finance, that is automatically worrying, because the consequences of any failure can ripple so widely and unpredictably. In a 2011 paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, Josh Lerner of Harvard Business School and Peter Tufano of Said Business School also argue that in a typical “S-curve” pattern, in which the earliest adopters of an innovation are the most knowledgeable, a widely adopted product is more likely to have lots of users with an inadequate grasp of the product’s risks. And that can be a big problem when things turn out to be less safe than expected.

Thursday, April 26, 2012

"Aja" Steely Dan 1977 LP

"Aja" was the first album for me that offered an optimistic feel about being alive. Not many albums have influenced us as much as "Aja." Fagen and Becker created a most unique flavor of Jazz, beautiful melodies, genius production and perfect performance blend to produce a masterpiece.

"I cried when I wrote this song, sue me if I play too long" This infamous lyric, out of Deacon Blues, typifies the Aja project. Having already achieved everything they wanted to accomplish in the public eye, The Dan started writing the music that was in their hearts. This was the beginning of a new era for Donald Fagan.

Simply one of the best albums ever. I've had the album since I was a kid and I never get tired of the music. Fusion jazz at it's finest. Thanks Donald Fagan. You to Walter B!!

"I cried when I wrote this song, sue me if I play too long" This infamous lyric, out of Deacon Blues, typifies the Aja project. Having already achieved everything they wanted to accomplish in the public eye, The Dan started writing the music that was in their hearts. This was the beginning of a new era for Donald Fagan.

Simply one of the best albums ever. I've had the album since I was a kid and I never get tired of the music. Fusion jazz at it's finest. Thanks Donald Fagan. You to Walter B!!

Saturday, April 21, 2012

Has Japan Passed tipping point? Part 1:

Some of the best-known research on financial crises asserts that countries get into trouble when debt-to-GDP ratios surpass 80%. With a national debt that now checks in at roughly 220% of gross domestic product, Japan, at least by rule of thumb, should have collapsed a long time ago. Yet Japan has — thus far — somehow avoided a debt crisis.

In fact, many investors have bet against Japan over the years . . . and lost. A common mistake over the past two decades has been shorting Japanese government bonds — trades which have mostly ended in a trail of tears. In a country where interest rates have moved slowly but consistently lower over the past two decades, investors who have gambled on the thesis that Japan’s financial structure is unsustainable have been forced to learn one of the harshest lessons of investing: There is little difference between being early and being wrong.

So, how exactly have interest rates in Japan remained so stubbornly low in the face of a persistently stagnant economy and high and growing debt? Why aren’t investors demanding higher rates of return? Can this economic anomaly continue? If so, for how long? If not, when does Japan cross the event horizon for a major shift in fortunes?

The answers to these questions have proven so elusive over the years that I figure it’s time to try to get to the heart of the matter. After all, it’s not just about Japan: A better understanding of Japan’s fragile economic imbalances sheds light on current events in Europe and the United States, which, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, have implemented policies similar to those that have been pursued by Japan.

The story begins with Japan’s post-war economic miracle. In order to rebuild its economy after the devastation of World War II, the Japanese government adopted an export model to boost export growth and import know-how. Japan invested heavily in education, research and manufacturing. A key element of the export model is, of course, accommodative monetary policy whereby a country uses credit creation, infrastructure development, and lower-than-market interest rates (known in monetary parlance as “financial repression”) to focus the country on exports. As the original “Asian Tiger,” Japan employed this strategy to great effect over the years, growing GDP sharply on the back of strong exports. As long as GDP and exports are growing, this model works. But when GDP stops growing and exports slow, the model fails. The point of failure for Japan was when its easy monetary policy stimulated a real estate and stock market bubble instead of fueling exports.

In 1985, the major economies of the world (United States, Japan, West Germany, France, and the United Kingdom) coordinated the Plaza Accord to reduce the value of the dollar relative to other major currencies (including the yen) with the specific intent of reducing trade imbalances. In the 24 months after signing the accord, the yen appreciated by 50%. By mid-1986, the rising yen had forced Japan into a recession (because the stronger yen harmed the country’s exports).

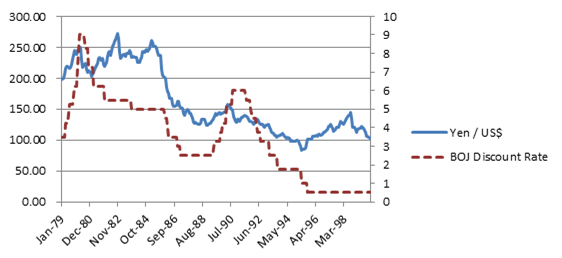

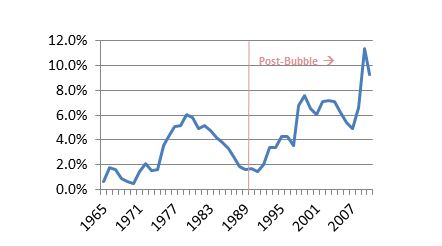

As illustrated by the dotted line in Figure 1, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) responded by reducing the official discount rate five times between January 1986 and February 1987, leaving it finally at 2.5% — which remained in effect until May 1989. The BOJ was ferociously trying to stimulate the economy with aggressive easing. In addition to low rates, the BOJ maintained high levels of money supply and credit growth, which drove the creation of the bubble as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Yen Exchange Rate and BOJ Discount Rate

Sources: Bank of Japan, CFA Institute.

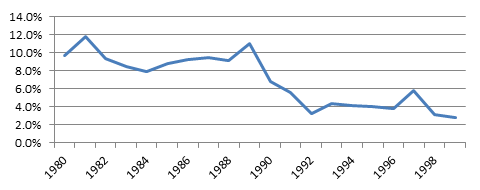

Figure 2: Percent Change in Money Supply (M2)

Sources: World Bank, CFA Institute.

The bubble manifested itself in both real estate and the stock market. It finally popped as the BOJ raised interest rates in 1989–1990, with historic collapses from which — even now, some 22 years later — the country has not recovered.

Nevertheless, Japan has been able to finance itself at extremely low rates during those 22 years. How? The financing of federal governments is much more complicated than the simple taxation of citizens. Governments finance themselves through some combination of direct taxation of citizens, taxation of businesses, tariffs on imports from other countries, build-up and usage of foreign currency reserves from international trade, issuance of debt, and money printing (if possible). Therefore, Japan’s ability to finance its federal government will be determined by the health of its GDP growth (which grows tax revenues, all else equal), its ability to grow federal tax revenues, its ability to control its budget, its ability and willingness to use its substantial foreign exchange reserves, and perhaps most importantly, its ability to continue selling bonds to the public. The secret of Japan’s ability to finance itself over the past 22 years is that it has used its current account surplus to create a closed loop — more money flows into Japan than flows out, and that net inflow is largely invested in JGBs (Japanese government bonds).

Here’s how it works: on the trade side, Japan exports more than it imports bringing more capital into Japan than leaving. Japan has maintained a trade surplus for about 30 years. And because of this persistent trade surplus, Japan has built up a large portfolio of foreign currencies. These foreign currencies are then invested in foreign assets (e.g., U.S. Treasuries) earning Japan a steady stream of income. Because this portfolio is large, Japan — as a country — regularly earns more income on its foreign currency holdings than they pay out to foreign investors. In combination, the trade surplus and the income surplus brings new money into corporate Japan. Corporate Japan places that money into the banking system, which then gets levered up and dramatically expands its purchasing power. Then the banks, life insurance companies, and pension funds turn around and buy lots of JGBs (accompanied with much pressure/regulation by the Bank of Japan).

In fact, the major banks, such as Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, Sumitomo Mitsui, and Mizuho, regularly buy JGBs — even viewing it as a “public mission” to support Japan. In addition, the Bank of Japan buys lots of JGBs on the open market, trying to drive up prices and drive down yields, thereby manufacturing low rates. While this monetization of debt creates inflationary pressures, it has thus far been offset by the deflationary pressures of a declining workforce and declining population. There are short-term fluctuations from year to year, but it is clear when looking at averages decade by decade that funding pressures in Japan have been growing over time.

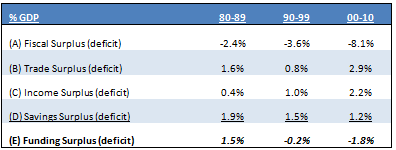

Table 1: Breakdown of Funding Surpluses/Deficits as a % of GDP

As you can see in Table 1, this is the answer to the original question. This cash flow cycle is how Japan has funded itself over the past 22+ years. Only now, the profile is changing. The Japanese debt crisis is being spawned by a burgeoning fiscal deficit. As the fiscal deficit has expanded, it has placed greater pressure on the Japanese government to sell debt and on the Bank of Japan to purchase it. Of course, the BOJ has been stepping in and buying JGBs when corporate demand has not been strong enough to keep rates low, as illustrated in Figure 3.

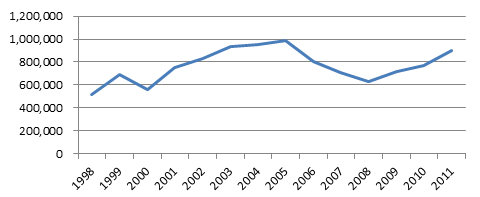

Figure 3: JGBs Owned by the Bank of Japan (in ¥100 mm)

Sources: Bank of Japan, CFA Institute.

Although Japan probably still is often thought of as a high-saving society, this is no longer true, at least for households. Japan’s household savings rate is now around 2% (down from a peak of 44% in 1990). So, in combination with chronic, large fiscal deficits, Japan’s low bond yields appear to present an oxymoron. However, Japan has also maintained a high corporate savings rate and low levels of fixed investment (both residential and nonresidential), making Japan a net exporter of capital. However, its fiscal profligacy is catching up with it: Its fiscal deficit has risen to more than 11% of GDP, where it remains today.

Up to now, Japan has been able to finance this funding deficit, as illustrated in Figure 4, primarily by issuing bonds. Historically, these bonds have been purchased by the public through various channels, ranging from household purchases to corporations to domestic banks to the post office. However, the aging of Japan’s population is altering the fundamental demand structure for bonds.

Figure 4: Japan: Bonds Issued as a Percent of GDP

Although the aging of Japan’s population has been much discussed over the years, it is just now beginning to manifest itself — and as people become old, they tend to spend their savings rather than accumulate more savings — a process known as dissaving. Ominously, Japan’s population declined for the first time in 2009 (and has been declining ever since). Already about 30% of Japan’s population is elderly; that figure is expected to grow to about 40% over the next 30 years or so. And given Japan’s welfare society system, their (shrinking) working-age population will save less and less as their burdens in supporting the dependent-age population (both young and old) grow more and more. According to a McKinsey study, savings rates in Japan decline markedly after people turn 50 years old. Given its demographic profile, Japan’s combination of aging and life cycle effects will continue unabated.

At present, Japan has just over 127 mm people. According to the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, Japan’s population — 20 years from today — will shrink to about 118 mm by the year 2032 (with an even greater deceleration in the working age population). Today, Japan’s GDP per capita stands at about ¥3.7 mm per person. Assuming they can maintain this level over time and keeping inflation neutral, Japan’s GDP would shrink from ¥476 trillion today to about ¥442 trillion in 2032. Given the ongoing massive fiscal deficits which Japan finances through similar levels of debt issuance, their national debt levels will rise to ¥2.4 quadrillion (rising from ¥980 trillion today). Another big question mark is of course interest rate levels. Even assuming their average interest cost on debt remains unchanged from today’s levels, Japan’s debt service will consume over 50% of the federal budget by 2032 (up from 23% today). With a populace that does not favor immigration, it seems that the die is cast. Japan will inevitably age and shrink — but not its debt.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)